“When I was first hired as Production Manager, I got a pretty negative impression of one of my Leads,” said José, even though his employee was older and had been at the plant longer. José explained, “His expertise was important to the production process, but all I ever heard from him were complaints about how things were run, like nobody would ever be able to fix anything and things were so messed up. I just decided he was grumpy and gave him a wide berth.”

José was put off by his employee’s remarks and actions, and also felt sorry for the guy because he knew the company had a history of neglecting its employees. But José was convinced that it would take a long time before this veteran employee “improved” his attitude and, as a new manager in the middle of turn-around, he didn’t have the luxury of time.

When we’ve got a business to run or work to do in the day-to-day grind it can be hard to slow down. The fast thinking we all do enables us to work efficiently and assess quickly whether a person, group, or situation is helpful or hurtful.(1)

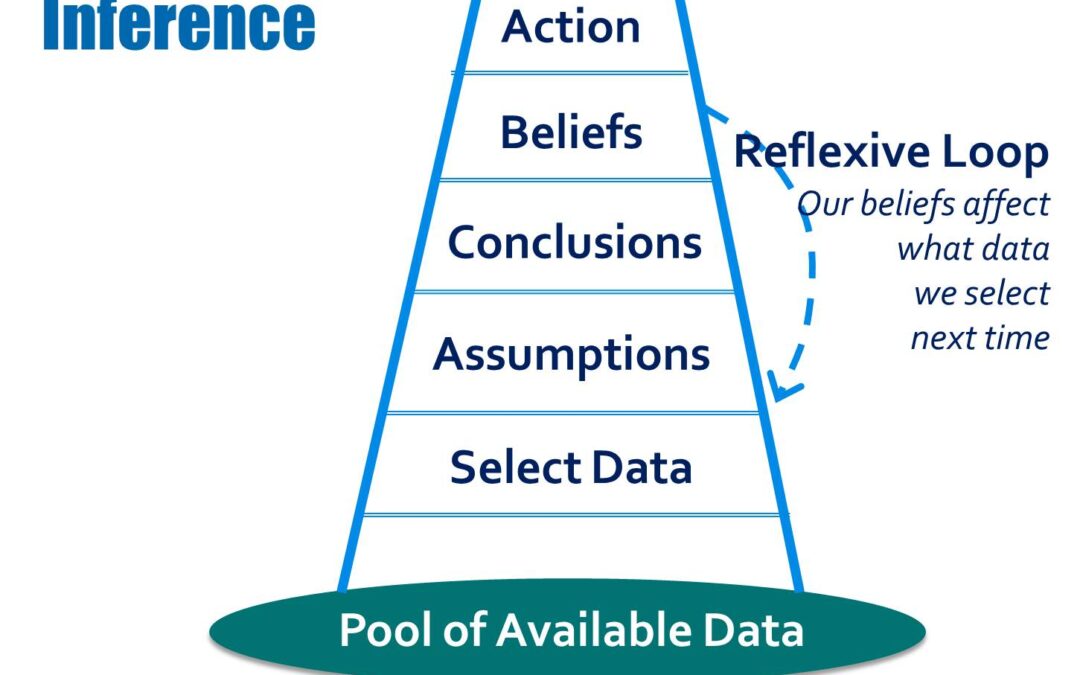

José needed to keep moving, so he made an assumption about his Lead and inadvertently started climbing the “Ladder of Inference.”

How fast thinking works

The Ladder of Inference has five steps. First proposed by business theorist Chris Argyris in 1970, it describes the thinking process that we go through, usually without realizing it, which moves from observation to action. The thinking stages can be seen as rungs on a ladder. Thinking fast, we…

- Select data because we can’t take in all that is presented to us at one time, we subconsciously choose what we should pay attention to

- Paraphrase data by putting the part we chose into our own words and applying our existing assumptions

- Name what’s happening and subconsciously generalize about that data point we chose

- Evaluate what’s happening as good or bad based on our value system and our existing theories

- Decide what actions to take that seem “right” because they are based on what we believe (2)

We can see that embedded in each step of this ladder of data selection and refinement is our unconscious bias. That bias is shaped by the culture around us. Being repeatedly exposed to images in movies, news media, stories, jokes, etc. within our culture reinforces reflexive data selection. In other words, we make assumptions about people and situations without even knowing it.

The ability to categorize people quickly and automatically according to social and other characteristics is a basic skill of the human brain that helps give order to life’s complexity and keeps us safe.(3) And because we all have a fundamental for order and safety, we can’t help but categorize.

However, because fast thinking is stereotyping and automatic, it’s also fallible, leading to inaccurate, often irrational conclusions and alienating actions.

Don’t climb the ladder

So we can choose to avoid climbing the Ladder of Inference altogether – by accepting the idea that we’re always going to make assumptions about what others say and do. It’s how people are. And if we didn’t draw on our past experience and own cultural context to help us interpret the world, we’d be lost; we wouldn’t be able to learn from our experience.

The trick, then, is to draw on our experience and context in a way that holds our assumptions in check.

We can…

- Reflect. Notice our assumptions, reasoning and reactions.

- Verify. Check back and see if we were clear about how we communicated with others about our thinking, reasoning and feelings

- Inquire. Ask questions about what others are thinking and feeling and test our assumptions for accuracy

What happened

Though definitely put off by his Lead’s complaints, José began to wonder if any of them were legitimate. His Lead had been with the company for decades and likely had insight that José could learn from. On his daily rounds, José decided to make a point to spend a few extra minutes with his Lead. José made sure he wrote down the Lead’s ideas (even if they sounded negative) and told him he’d either get an answer or get the idea to a person who could address the issue. In each case, José made it a point to circle back with him the same day and give him some type of report to demonstrate his concern.

When I asked him what happened, José said, “It actually didn’t take long before his attitude began to change; he began to smile when I came around. He stopped just pointing out negative stuff; he pointed out problems but also offered solutions. After just a few weeks, he was more productive and a nicer guy to have around. And I felt better about my leadership.” The Lead’s behavior and demeanor had changed when his younger boss took the time to ensure that his employee felt valued and heard.

Working to ensure an employee feels valued and heard is Cultural Intelligence in action. Cultural Intelligence is the ability to appreciate another’s perspective and change our behavior to show genuine respect across differences of generation, gender, race, nationality or education-levels.

Within the context of our crises of pandemic and protesting, its particularly important that employees feel valued, heard and engaged. When I speak with clients, I’ve heard time and again how social distancing is causing both workers on factory floors and mangers in home offices to feel isolated and alone. Now more than ever we need our Cultural Intelligence to recognize and affirm a person’s experience so that our employees can know and feel that they are a valuable part of our community.

What a leader can do

Leaders and their teams can inadvertently hinder their growth by climbing the Ladder of Inference and restricting themselves to data that support their existing assumptions. This may lead to inadvertently ignoring contradictory data that might be vital to relationships, collaboration and innovation.(4)

If we think we know what someone is going to say or do, we’re already near the top of the ladder. Leaders can be aware that embedded assumptions can hinder our ability to connect with people, practices and information and can stifle inquiry.

So to summarize, leaders, the better option is to slow down and…

- Reflect. Notice our own and the group’s assumptions, reasoning and reactions

- Accept. Realize that meaning and assumptions are not reality but perception

- Model. Make our thought processes visible to others

- Inquire. Ask what others are thinking and feeling and what they see differently

- Wonder. Consider the source and other possible interpretations of the data

- Verify. Cross-check that assumptions are based on the data they’ve gathered

It’s counter-intuitive, in the urgency we can feel in Western cultures, that slowing down is a more efficient approach to problem solving. But to increase collaboration and productivity in our organizations, it’s important to take a few extra minutes within our formal and informal meetings to recognize and affirm the unique experiences and wisdom of our colleagues and direct reports. That’s the beauty of Cultural Intelligence brings to any organization; when we take the time to get down off the Ladder of Inference, leaders and employees feel valued, heard and engaged and the organization realizes more collaboration, productivity and innovation. -Amy S. Narishkin, PhD

References:

- Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow, New York: Macmillan.

- Senge, P. (2006). The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday http://sacdialogue.com/LadderofInference.pdf

- Frith, U. (2015) Unconscious bias. The Royal Society: https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/publications/2015/unconscious-bias/

- Labrie, P. Mental Models – Ladder of Inference https://artofleadershipconsulting.com/blog/leadership/mental-models-ladder-of-inference/