The phrase “talking turkey” usually refers to speaking frankly, discussing hard facts, or getting down to business. “Turkey” by itself has a number of meanings. Of course, it’s known primarily as the big-feathered awkward bird almost 90% of Americans enjoy during their Thanksgiving feast. While taking home a turkey is considered a brag-worthy feat, being called one is not. It’s considered an insult.

Today there’s a lot of “talking turkey,” especially in boardrooms, congressional hearings and in political debates – one more reason why, during the holidays, it’s nice to just sit back, relax and eat the turkey.

This year many of us can be thankful for being alive and for the support we have found in one another. But how do you sit back, relax and enjoy talking especially in trying times like these? Our country and conversations are pretty divided but does our family dinner or Zoom call have to be?

I’m glad you asked.

One of the ways to get at the answer is to consider our surrounding culture: Is it task-based or relationship-based? In dominant American culture it is so much the former. We can get so caught up in our to-do lists, sometimes it doesn’t even occur to slow down and listen to one another. Yet, as human beings we have a deep need for human connection. When we don’t take the time to connect with ourselves and one another, we can feel isolated and alone, even in a crowded room.

How to connect

To connect with another, you need to “see” the other by accepting their feelings and experience as legitimate, even when their experience is different from your own. How do you do that?

When family or friend brings up a topic that is off-putting or hurtful to you, slow down, take a deep breath and notice your assumption. Even if they get your ire up, notice how they’ve struck a chord, acknowledge your internal reaction and temporarily hold off from expressing it out loud. Let them finish talking. How you feel is important. So is what they’re saying. While they’re talking and you’re feeling, imagine how they feel. When they’re finished, you can name that emotion you sense they feel. You don’t have to agree with their opinion or even completely understand, but you can affirm their feelings and experience. You can say something like:

- “Sounds like you’re mad.”

- “That must have been tough.”

- “It’s disappointing when someone doesn’t understand.”

It can also help to learn more about where they are coming from. Abraham Lincoln said, “I don’t like that man. I must get to know him better.” With a posture of curiosity, you can learn another person’s story by gently requesting more information. You can ask something like:

- “May I ask you a question?”

- “What happened to you?”

- “What was that like?”

What I learned

In a coaching session, I learned from a young military veteran. He was recently retired, having just completed two tours of duty in Afghanistan. When I heard his background, I thanked him for his service. He didn’t respond so we moved to another topic. Later on in the conversation, I asked, “May I ask you a question?” He nodded. “I noticed you were quiet when I thanked you for your service. Would you help me understand what made you quiet?

As I listened to his story about Afghanistan, I could not even imagine what it was like to be so far from home, in such a vastly different place, fighting for your life day in and day out for over a year, only to do it all over again. The experience had not left him in a good place. After he related his story and I affirmed his feelings and experience, he told me he had not spoken much about his service until this point. He said he was feeling relieved. He thanked me for listening and the work I was doing.

He went on to explain that it hurts when people thank him for his service because, right or wrong, he struggles with the fact that some people in the military have jobs that don’t put them in harm’s way but people thank them with the same words.

I said, “That’s tough. It sounds like it comes across as dissmissive.”

He said, “It does.”

I said, “I’m sorry I sounded dismissive. Thanks for teaching me. It sounds like, if I thank someone for their military service, I have an opportunity to learn how those words impact the person. I can say, ‘Thank you for your service to our country. Then I can ask, ‘How do my words impact you?’”

He said, “I think that would be good to check your impact. How did you learn to do this work?”

Conclusion

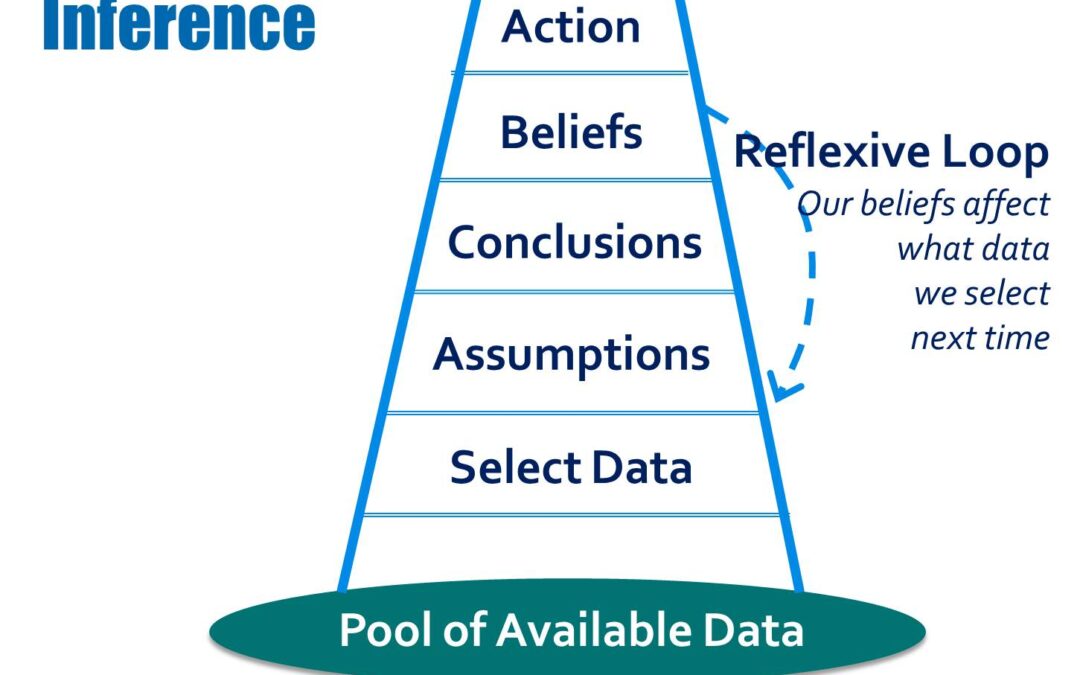

I’m not always successful creating a connection, particulalry when I’m tired or hungry. But when my needs are met, I’ve discovered this posture of learnng is what enables me to create genuine human connection. The best part is when you take the time to learn and honor other person, they often want to hear your story too. Though you may not agree with their politics or be able to relate to their experience, you can affirm their feelings as legitimate. It may take a few minutes or 15 minutes, but hear them out, ask if you can ask and then ask what happened. Together, you and the other person can develop a shared understanding, both differentiating and integrating your ideas.

Working together to develop a shared understanding is cultural intelligence in action. Cultural intelligence allows you to stand in solidarity with another, communicating you are not alone. Listening and affirming another’s experience is one of the greatest gifts we can give each other, not just during the holiday season but throughout the year. -Amy Narishkin, PhD

If you enjoyed this article, please share it. If you’d like to learn to feel more confident talking and working with just about anyone, you can take my self-study course. In just six 30-minute lessons you can have a full tool box of tools to create genuine human connection.